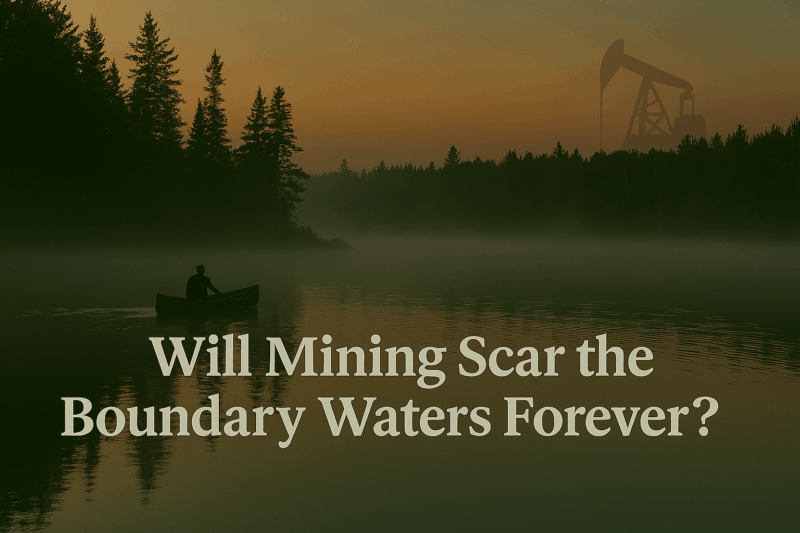

Introduction: A Wilderness Under Siege in Minnesota’s North Woods

In the misty veil of Superior National Forest, where ancient pines whisper secrets to paddlers gliding across 1,000 mirror-like lakes, Becky Rom has stood sentinel for decades. At 76, the national chair of Save the Boundary Waters, Rom—granddaughter of a miner, daughter of an outdoor pioneer—embodies the soul of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW), America’s most-visited wild expanse. Yet on September 29, 2025, as the Trump administration accelerates approvals for a controversial copper-nickel mine adjacent to its shores, Rom’s lifelong vigil feels like a race against time. Twin Metals Minnesota’s proposed $1.8 billion project promises jobs but threatens sulfidation pollution that could scar this 1.1 million-acre sanctuary forever. For families like the Andersons—dad guiding his kids’ first portage, evoking Rom’s own wolf-pet Wisini days—this isn’t policy debate; it’s a heartbreaking crossroads, where economic dreams clash with ecological heirlooms, pitting progress against the pristine pulse of a frontier reborn.

The Human Toll: Lifelong Guardians and Families Facing Loss

Becky Rom’s fight began in middle school, poring over maps of the BWCAW’s labyrinthine waterways, her family’s pet wolf Wisini a living emblem of untamed bonds. Now, as Twin Metals drills test holes near Birch Lake, Rom’s voice trembles with urgency: “This isn’t just land—it’s legacy, where my grandfather mined honorably, but this sulfide poison could kill what we cherish.” For locals like 42-year-old guide Sarah Knutson in Ely, who leads 200 annual trips for families escaping urban grind, the mine’s shadow looms personal: “My kids learn to fish these waters; if acid rain turns them toxic, what stories do I tell then?” Knutson’s husband, a former miner, weighs the 700 promised jobs against fears of “dead lakes like the Iron Range’s scars.”

Opponents’ grief runs deep: Indigenous Ojibwe elders, whose treaties birthed the 1978 Wilderness Act protecting the BWCAW, invoke ancestral waters poisoned by past mines. Ely’s 3,000 residents, tourism-dependent (BWCAW draws 250,000 visitors yearly, $1.2B economic boon), split along generational lines—youth like 19-year-old activist Mia Thompson rallying petitions (50K signatures), elders haunted by 1920s logging ghosts. In this human tapestry, the mine isn’t abstract; it’s a fracture—families torn between paychecks and purity, guardians like Rom bearing the weight of a wilderness that feels like kin.

Facts and Figures: The Mine’s Shadow Over the Boundary Waters

Twin Metals’ open-pit mine, slated for 20 years on 2,300 acres near Babbitt, would extract 275,000 tons of copper-nickel ore annually—critical for EVs and renewables—yielding $1.8B in value. Yet the U.S. Forest Service’s 2023 assessment warned of “catastrophic” sulfide risks, potentially acidifying 100+ miles of waterways. The BWCAW, a 1.1M-acre mosaic of lakes (1,090), rivers, and 2,000 campsites, hosts 250K visitors yearly—more than Yellowstone—its oligotrophic waters teeming with 70 fish species, loons, and moose.

Key data points:

| Aspect | Pro-Mine | Anti-Mine |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Impact | 700 direct jobs ($80K avg. salary); $500M state revenue over life | Tourism loss: $1.2B/year; 5,000 jobs at risk |

| Environmental Risk | “State-of-art” wastewater tech; no spills in 20 yrs (company claim) | Sulfide pollution: Acid mine drainage could kill fish in 10-50 yrs (USGS) |

| Regulatory Status | Trump admin fast-tracks via 2025 EO; ROD expected Q1 2026 | Biden 2023 withdrawal; lawsuits from 10+ groups pending |

| Visitor Stats | BWCAW: 250K/year (up 20% post-COVID) | Pollution precedent: 1990s mines acidified 200 lakes nearby |

| Mineral Need | 40% U.S. copper deficit; key for green tech | Alternatives: Recycling, imports from Canada/Australia |

The Forest Service’s 2023 EIS deemed mining “feasible,” but a federal judge halted it in 2024—now overridden by Trump’s “critical minerals” push.

Broader Environmental Context: A Flashpoint for Wilderness vs. Minerals

The BWCAW, carved from 1964’s Wilderness Act as a “forever wild” haven, stands as a crown jewel—1.1M acres where motors yield to paddles, its peatlands storing 10% of U.S. carbon. Twin Metals’ sulfide-ore mining, unlike taconite pits, risks eternal acid drainage, as seen in Michigan’s Eagle Mine (fish kills since 2014). Trump’s EO, invoking Kirk’s assassination to justify “energy dominance,” accelerates approvals amid global mineral scrambles—China controls 80% of nickel processing—pitting climate goals against conservation.

Critics like Rom decry “industrial invasion,” citing 2023 USGS models predicting 90% lake acidification within decades. Proponents, including Iron Range miners, argue “responsible mining” with $100M bonds for cleanup. Nationally, it echoes Alaska’s Pebble Mine saga (blocked 2023), where 70% public opposition prevailed; globally, Indonesia’s nickel boom poisons reefs, urging U.S. alternatives like deep-sea mining bans. For Ely, where tourism rivals mining’s $200M legacy, it’s existential: A wilderness drawing 250K souls yearly, or pits scarring the soul of the North Woods?

What Lies Ahead: Legal Standoffs, Community Compacts, and Carbon Crossroads

With Trump’s ROD looming Q1 2026, Save the Boundary Waters eyes Supreme Court appeals, backed by $5M in donations. Ely hosts forums—Rom’s group partners with miners for “green extraction” pilots, testing low-impact tech. Federal incentives ($500M IRA funds) could fund water monitors; locals push eco-tourism expansions, like $10M trail grants.

Resilience blooms in hybrids: Community benefit agreements ensuring 50% local hires, wetland buffers. Globally, Sweden’s Kiruna mine relocates towns sustainably—inspires BWCAW compacts. For Knutson’s kids, it’s hope: Paddles over picks, if voices like Rom’s prevail. Success? A balanced Boundary—minerals mined mindfully, wilderness wild eternally.

Conclusion: Safeguarding the Boundary Waters from Mining’s March

As Becky Rom’s middle-school maps fade against Twin Metals’ blueprints, the Boundary Waters’ fate teeters—a pristine paradise menaced by mining’s metallic lure. In this clash of copper dreams and canoe trails, Trump’s rush risks poisoning a legacy for generations. Yet Rom’s unyielding stand, echoed in Ely’s divided hearts, reminds us: Wilderness isn’t won with wealth alone, but wisdom. May the BWCAW’s waters run clear, its loons unbroken—a testament to America’s wild heart, forever free.